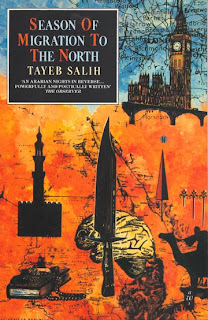

Season of Migration to the North, by Tayeb Salih

This extremely intriguing passage comes along late in the book, but what I have quoted gives away nothing of the mystery and enigma, though it reveals something I found at the heart of the book which I found more curious even than the charismatic figure of Mustafa Sa'eed.

This extremely intriguing passage comes along late in the book, but what I have quoted gives away nothing of the mystery and enigma, though it reveals something I found at the heart of the book which I found more curious even than the charismatic figure of Mustafa Sa'eed.I became bored with reading the bits of paper. No doubt there were many more bits buried away in this room, like pieces in an arithmetical puzzle, which Mustafa Sa'eed wanted me to discover and to place side by side and so come out with a composite picture which would reflect favourably upon him. He wants to be discovered, like some historical object of value. There was no doubt of that, and I now know that it was me he had chosen for that role. It was no coincidence that he had excited my curiosity and had then told me his life story incompletely so that I myself might unearth the rest of it. It was no coincidence that he had left me a letter sealed with red wax to further sharpen my curiosity, and that he had made me guardian of his two sons so as to commit me irrevocably, and that he had left me the key to this wax museum. There was no limit to his egotism and his conceit; despite everything, he wanted history to immortalize him. But I do not have the time to proceed with this farce. I must end it before the break of dawn and the time now was after two in the morning. At the break of dawn tongues of fire will devour these lies. (154)This is the narrator speaking, looking through some writing left by Sa'eed. What is interesting to me about this passage is the centrality of the word "discover," which appears twice here. This word or one of its inflections makes four other appearances in the book, uses which guide us to how to think of its presence above.

The wife of Sa'eed's patron, a sort of mother-figure to Sa'eed, writes to the narrator of her husband: "I shall write of the splendid services Ricky rendered to Arabic culture, such as his discovery of so many rare manuscripts, the commentaries he wrote on them, and the way he supervised the printing of them" (148). The narrator also finds an old newspaper which informs him that many years ago, "The Discovery, Captain Scott's ship, has returned from the Southern Seas" (150). And elsewhere in the book, the word is used twice to suggest an interior exploration: Sa'eed says of his childhood, "Soon I discovered in my brain a wonderful ability to learn by heart, to grasp and comprehend" (22), and the narrator describes one of Sa'eed's relationships with British women: "Then she met him and discovered deep within herself dark areas that had previously been closed" (140).

It probably does not require this exhaustive accounting to note that "discovery" has a distinctively Orientalist connotation, a sort of mass delusion that the initial moment of white presence in some non-white sphere constitutes a "discovery," regardless of whether the "discovery" happened to be common knowledge or even practical knowledge among a non-white people. It is a Romantic foolishness which Sa'eed is particularly given to after his migration to England, and I think that Salih is suggesting in the long passage I quoted above that Sa'eed has largely orientalized himself into an inscrutability (fragments which portend a whole but do not create it), that even his return to the Sudan and his self-imposed solitude and exile is completely contained, contaminated by the orientalism he made such devastating use of while in England to capture the notice and inflame the desires of the English. Sa'eed is his own best Edward FitzGerald, and that fact is marvelously destabilizing for the text and for the reader—how do you begin to read him otherwise?

The way that Salih keeps the reader circling Sa'eed, and complicates this movement by the interferences of the narrator is, as one critic noted, Conradian, and it is absolutely worthy of that comparison. It is a fast book even more than it is a brief book, and its pace creates extraordinarily powerful delayed-reaction recognitions of what, precisely, are the stakes and the import of its narrative.

I actually had put Season on my queue before Salih died, but I moved it up when I read some of the tributes to him (thanks, Aaron!). I am now sort of dismayed and bewildered by the fact that he wasn't much more famous, that this book isn't considered an immovable cornerstone of contemporary world literature along with Cien Años de Soledad, Midnight's Children and Things Fall Apart. Of course, my ignorance of it is entirely cultural: it is not as if it doesn't have that valuation elsewhere, and the lifting of my ignorance does not betoken a restitution of a hidden gem to its rightful place. Read it, enjoy it, but don't call it a discovery.

Comments

I'm sure the NYRB release will at least be easier and cheaper to obtain, but it's the same translation, which is too bad--I know Johnson-Davies is a big name in translation from Arabic, but I found his prose the least appealing part of the book (though more than compensated for by the structural and intellectual brilliance of the ideas contained). Furthermore, Laila Lalami is the NYRB's guest essayist, which is really disappointing to me--I don't want to be like Stephen Mitchelmore and trash someone's review of The Kindly Ones simply because it was negative, but she basically paraphrased Michiko Kakutani's panning, with not a single original thought.

Compare:

Lalami: http://www.latimes.com/features/books/la-ca-jonathan-littell15-2009mar15,0,6817045.story

Kakutani: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/24/books/24kaku.html

Ugh. This is why I don't feel newspaper book review sections declining is a peril to the republic.

(Incidentally, I don't think it's right to assume Steve has problems with reviews of The Kindly Ones because they're negative, but with the quality of the reviews themselves, the nature of the reading.)

I don't mean to say that those books aren't central for very good reasons, just that I found (and I think you also find) Season to have equally compelling reasons to be considered on their level. But your suggestion about the Conradian elements seems right to me--I can imagine encountering difficulties building a syllabus that finds a convenient home for Season.

I wonder if Sa'eed's personal choices with white women might qualify as a kind of masking (as African Americans would call it). Consider this quote by Ralph Ellison:

"And yet I am no freak of nature, nor of history. I was in the cards, other things having been equal (or unequal) eighty-five years ago. I am not ashamed of my grandparents for having been slaves. I am only ashamed of myself for having at one time been ashamed. About eighty-five years ago they were told that they were free, united with others of our country in everything pertaining to the common good, and, in everything social, separate like the fingers of the hand. And they believed it. They exulted in it. They stayed in their place, worked hard, and brought up my father to do the same. But my grandfather is the one. He was an odd old guy, my grandfather, and I am told I take after him. It was he who caused the trouble. On his deathbed he called my father to him and said, "Son, after I'm gone I want you to keep up the good fight. I never told you, but our life is a war and I have been a traitor all my born days, a spy in the enemy's country ever since I give up my gun back in the Reconstruction. Live with your head in the lion's mouth. I want you to overcome 'em with yeses, undermine 'em with grins, agree 'em to death and destruction, let 'em swoller you till they vomit or bust wide open." They thought the old man had gone out of his mind. He had been the meekest of men. The younger children were rushed from the room, the shades drawn and the flame of the lamp turned so low that it sputtered on the wick like the old man's breathing. "Learn it to the younguns," he whispered fiercely; then he died."

The idea of "overcom[ing] 'em with yeses" was something Sa'eed learned to do in the North. And it characterized his relationship with a certain group of women and white liberal intellectuals (the more perceptive of whom - like the technocrat Richard - recognize his game, but don't see the mask). I suppose the reason Jean Morris is so central to Sa'eed's life is because she is the one person - woman - whom he cannot control, or control himself around. And in the end he kills her for it.

Is it evidence of Sa'eed's "Africanized orientalism"? I'm not so sure. If nothing else, Sa'eed is a thinker. He's aware of his choices, which he makes conscientiously, and with politics always in mind. ("I am not Othello. Othello was a lie.")

Of course, Sa'eed also calls himself a lie at one point. And I suppose Ellison's grandfather-figure was lying, too. But there's a strategic, subversive element in playing to the stereotypes of the powerful (like Br'er Rabbit).

I haven't quite figured out where Jean Morris fits within all this. Because if anyone confirms your insights about Sa'eed fragmenting himself, orientalizing himself, it is she. More than anything, though, I see Mustafa Sa'eed as representative of the fate of a certain cohort of black public intellectuals of this period (both in Africa and the diaspora). If these men (unfortunately, they were almost all men) were making choices, conscientiously, politically, the fact that they couldn't completely escape the specter of this other fate - which you so deftly point out - is perhaps the ultimate tragedy.

And of course, we don't know the ultimate fate of these figures - the novel leaves them (and us) on the precipice, in the doorway waiting...