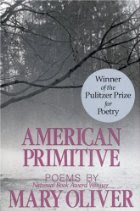

American Primitive, by Mary Oliver

I posted what I think was the volume's best poem, the simply named "Cold Poem," a couple of days ago. I suppose I liked it because it seems to me the least like a "nature poem," although it is uses natural metaphors to speak to humanity.

I posted what I think was the volume's best poem, the simply named "Cold Poem," a couple of days ago. I suppose I liked it because it seems to me the least like a "nature poem," although it is uses natural metaphors to speak to humanity.Let me just lay my cards on the table. I didn't enjoy the bulk of this slim volume and I'm afraid I may just dislike "nature poetry" or "nature writing"—I think trying to read Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek gave me a cold. Now, I am very aware that this is a very meager sample and that there is a range of styles and approaches to writing about nature. I am not trying to write off the whole kittencaboodle. (Actually, come to think of it, I really do like Robinson Jeffers and those poems of Robert Hass's which could be considered nature poems). I just really don't like most of what I read in American Primitive. It doesn't speak to any experience of nature I've ever had, and to be honest, I found a lot of it silly.

These are, for me, the characteristics of most of the poems in American Primitive:

- a drowsy, unaroused sensuousness

- a bland, sober, stale, becalmed sort of mysticism that only just flowers past austerity and seems ignorant of intoxication

- catalogues like none Whitman ever wrote or wanted to write, lacking dynamics—one could almost substitute a grocery list from a farmer's market and achieve similar results

- an indifference to duality or to opposition—one particular thing that irritated me was the way that fire and water are characterized almost interchangeably throughout the volume—both are gentle, flowing things that cover up or fill nature benignantly ("They poured / like fire over the minnows, / they fell back through the waves / like messengers / filled with good news" - "Bluefish")

- the belief that description of nature constitutes a state of wonder, that artistic wonder is effectively bought for the same price as natural wonder and requires no extra effort

- a strange belief in a sort of conservation of matter, where nothing natural and beautiful is ever truly lost ("you float into and swallow the dripping combs, / bits of the tree, crushed bees — a taste / composed of everything lost, in which everything / lost is found." - "Honey at the Table")

Mary Oliver's love of nature seems limited to appreciating the fact that she sees it, which doesn't really require anything more of the world, the reader or herself than that nature be preserved in at least a few places where we can take pleasant walks. This form of appreciation can also be done almost as easily in retrospect as in action, so there's barely any motivation to preserve even that. These lines come late in the book and seem to be a sort of creed:

To live in this worldThis is the basic sentiment embodied in her poem "John Chapman," about Johnny Appleseed: "you do / what you can if you can; whatever // the secret, and the pain // there's a decision: to die, / or to live, to go on / caring about something." I'm reminded of Eisenhower's famously ambivalent statement, "Our government makes no sense unless it is founded on a deeply held religious belief – and I don’t care what it is." (For a good evisceration of that religious principle applied to literature, read James Wood's review of Updike's "Complacent God" in The Broken Estate.)

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.

I find this whatever-ethic artistically deficient in the general case, but unacceptable in the case of nature poetry or poetry which calls on nature for its subject or its inspiration. Deriving beauty from specifics, from individual moments and individual organisms or individual geological structures has long been the energizing force for poetry about the natural world, and the ethical generalities Oliver submits herself to are deeply at odds with the ontological specifics necessary for this powerful poetry, the individual herons and moles and snakes which she nevertheless tries to invoke. A nature poet to be artistically effective must, I deeply believe, be ethically committed in concrete, specific ways to nature and to express that through her poetry, or else the poetry is meaningless. If there is enough meaning to individual organisms to use them poetically, there must be enough meaning to make a political claim for their protection. If not, I'm not sure why you're writing about them.

"Cold Poem" is a little different. There is an acknowledgement of the price of life—the death of others ("we grow cruel but honest; we keep / ourselves alive, / if we can, taking one after another / the necessary bodies of others, the many / crushed red flowers")—and consequently there is also an implied acknowledgement of the ethical entanglements this situation yields. There is also a poetic concreteness to this understanding—the shark and seals (which stood out to me for obvious reasons—I am fond of my Seal namesakes) and the crushed red flowers. These images take their power from the fact that they exist in the poem not merely as metaphors (generalized, interchangeable with any other apposite image) but as synechdoches—the part for a whole. They do stand for something concrete, even as they also stand for something abstract, general.

The poem treats these acknowledgements and perhaps this concreteness as seasonal occurrences, coming on with the winter, the cold. The problem is, Oliver is not in this season very often; she is, I suppose, rarely cold enough.

Comments

Rae Armantrout - Next Life

Marianne Boruch - Grace, Fallen from

Kay Ryan - The Niagara River

Sarah Hannah - Inflorescence

A.E. Stallings - Hapax

Now when I read poetry, I read Adam Zagajewski (Eternal Enemies). To me, he's the reincarnation of Rilke. He transcends his contemporaries in the same way Oliver epitomizes them.

Mary Oliver poems. Her work is not trying to serve what you or I consider the purpose of nature to be. If you think that using a specific animal as a metaphore needs to serve a specific purpose and make a political claim for their protection then you have over analyzed the very simplicity that her work calls for. However I understand how her writing style as a whole may appear repetitive. As she gets older her poems realter more to nature then her earliest works. This ties into her own aging. Her diction is unique, and her poems reach those who can fully appericate their subject.