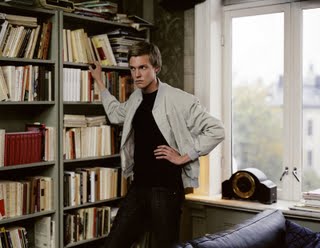

Reprise, Joachim Trier (2006)

The experience of watching coming of age films as one is actually coming of age is well-suited for embarrassment. E.g., I own (somewhere—I hope I lost it) a copy of Zach Braff's Garden State. I had a better than tepid reaction to The Rules of Attraction. I had a Rushmore poster for years.

And so by the time I watched Reprise, I had learned not to trust my instincts, a condition which made watching the film both sort of pleasantly difficult and unpleasantly easy. Reprise seemed (and probably was) tailor-made for me or for people (or let's be honest, for young men—like other sadyoungliterarymen tales, this one is shameless about its gender exclusivity) like me, even though it also initiated a quiet burst of self-evaluation and more than a little self-doubt—I knew I could not entirely trust my instincts regarding it, but how little could I trust them?

The film is about the triumphs and travails of two aspirant authors—young, handsome, privileged and not uncomfortable about it—as they effectively live out Keats's sonnet:

The ambivalence and self-doubt of the poem is well reflected in the film: there is—on both the characters' and the director's part— a constant wavering between assertions of true brilliance and tremulous acknowledgments that what looked at first to be brilliant may be merely clever. Bids for virtuosity, as in the opening scene, get reined abruptly in, only to be loosed once more on different, maybe only slightly less ambitious grounds. Let's take a look at the opening scenes (skip to the 0:45 mark—you'll bypass the corporate logos):

The way the collaborative reverie of the two writers is cut off abruptly into the title card will likely induce a laugh, especially as it cuts short the increasingly ludicrous ambitions of the swelling fantasy (a revolution in East Africa?). Then we are back (a reprise!) at the post-box, waiting for the young men to drop their manuscripts in, and the rest of the film is, effectively, the "reality" that replaces their reverie.

Yet the film itself—and the characters' actual lives themselves—is unsubtly ambitious, not so much a retraction as a very slight chastening of the initial, boundless dream. While the film depicts disillusionment, the film itself is not a disillusioning experience or process; it never retreats into irony and only mutters a terse apology for its earnestness. The bulk of the film—the lives as the characters live them—is a reprise of the opening sequence, and that can be winked at but need not be disavowed.

So this all is far from Braffian "The Shins will save your life" shallow oh-so-meaningfulness, but the question that haunts the film—or haunted this viewer at any rate—is how far—is the distance a clever distance, a knowingness that folds over into self-knowingness, a knowledge of the self-indulgence and self-absorption that prompts these very questions? Or is it far enough away—above maybe—to be brilliant, a distance at which self-indulgence and self-absorption are, if not fully justified, then at least suitable to the material?

What the film depicts so well—and what makes it both uncomfortable and pleasantly familiar—is the instability and recursiveness of these two questions—clever? brilliant? It is almost impossible to watch the film without asking these questions about oneself, and about one's relation to the film—is the distance from me to the film a clever distance, or am I far enough away to be brilliant?

I suppose these questions are not very polite, or gracious, or very wise to be explicit about. But the posing of them is, I hope, a part of maturation, rather than a defense against it. One could not really imagine a young man's realm more antipodal to the world of Reprise than Seth Rogen's collected works. Taking one's measure against the facts and products of the world and of other minds in some manner, though it may devolve into occasional petty posturing or occasional complete lapses of judgment, seems like the only way one can ever finally measure up, can figure out how to interact with those other minds, moving not beyond them but into their conversations. The objective, it seems to me (although what do I know?), is to obviate the felt necessity of "clever-or-brilliant?" calibrations of the self in and to the world and to actually engage with it. Reprise does not, I think, quite imagine that, but it points the way.

And so by the time I watched Reprise, I had learned not to trust my instincts, a condition which made watching the film both sort of pleasantly difficult and unpleasantly easy. Reprise seemed (and probably was) tailor-made for me or for people (or let's be honest, for young men—like other sadyoungliterarymen tales, this one is shameless about its gender exclusivity) like me, even though it also initiated a quiet burst of self-evaluation and more than a little self-doubt—I knew I could not entirely trust my instincts regarding it, but how little could I trust them?

The film is about the triumphs and travails of two aspirant authors—young, handsome, privileged and not uncomfortable about it—as they effectively live out Keats's sonnet:

When I have fears that I may cease to beLove and fame—absolutely.

Before my pen has glean'd my teeming brain,

Before high-piléd books, in charact'ry,

Hold like rich garners the full ripen'd grain;

When I behold, upon the night's starr'd face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love;--then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

The ambivalence and self-doubt of the poem is well reflected in the film: there is—on both the characters' and the director's part— a constant wavering between assertions of true brilliance and tremulous acknowledgments that what looked at first to be brilliant may be merely clever. Bids for virtuosity, as in the opening scene, get reined abruptly in, only to be loosed once more on different, maybe only slightly less ambitious grounds. Let's take a look at the opening scenes (skip to the 0:45 mark—you'll bypass the corporate logos):

The way the collaborative reverie of the two writers is cut off abruptly into the title card will likely induce a laugh, especially as it cuts short the increasingly ludicrous ambitions of the swelling fantasy (a revolution in East Africa?). Then we are back (a reprise!) at the post-box, waiting for the young men to drop their manuscripts in, and the rest of the film is, effectively, the "reality" that replaces their reverie.

Yet the film itself—and the characters' actual lives themselves—is unsubtly ambitious, not so much a retraction as a very slight chastening of the initial, boundless dream. While the film depicts disillusionment, the film itself is not a disillusioning experience or process; it never retreats into irony and only mutters a terse apology for its earnestness. The bulk of the film—the lives as the characters live them—is a reprise of the opening sequence, and that can be winked at but need not be disavowed.

So this all is far from Braffian "The Shins will save your life" shallow oh-so-meaningfulness, but the question that haunts the film—or haunted this viewer at any rate—is how far—is the distance a clever distance, a knowingness that folds over into self-knowingness, a knowledge of the self-indulgence and self-absorption that prompts these very questions? Or is it far enough away—above maybe—to be brilliant, a distance at which self-indulgence and self-absorption are, if not fully justified, then at least suitable to the material?

What the film depicts so well—and what makes it both uncomfortable and pleasantly familiar—is the instability and recursiveness of these two questions—clever? brilliant? It is almost impossible to watch the film without asking these questions about oneself, and about one's relation to the film—is the distance from me to the film a clever distance, or am I far enough away to be brilliant?

I suppose these questions are not very polite, or gracious, or very wise to be explicit about. But the posing of them is, I hope, a part of maturation, rather than a defense against it. One could not really imagine a young man's realm more antipodal to the world of Reprise than Seth Rogen's collected works. Taking one's measure against the facts and products of the world and of other minds in some manner, though it may devolve into occasional petty posturing or occasional complete lapses of judgment, seems like the only way one can ever finally measure up, can figure out how to interact with those other minds, moving not beyond them but into their conversations. The objective, it seems to me (although what do I know?), is to obviate the felt necessity of "clever-or-brilliant?" calibrations of the self in and to the world and to actually engage with it. Reprise does not, I think, quite imagine that, but it points the way.

Comments