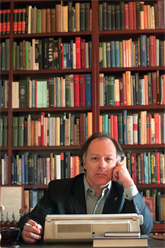

Javier Marías

The Spanish novelist Javier Marías visited New Haven this Wednesday, and I attended his reading/q&a. I usually find these things not terribly illuminating; the writer is usually cagey, and the questions are generally fawning and/or superficial. Or completely left-field.

The Spanish novelist Javier Marías visited New Haven this Wednesday, and I attended his reading/q&a. I usually find these things not terribly illuminating; the writer is usually cagey, and the questions are generally fawning and/or superficial. Or completely left-field.Marías was not cagey; in fact, he was much more candid than I would have anticipated. He seemed completely comfortable noting autobiographical correspondences with his characters or with events in his books (e.g., the girl's suicide at the beginning of A Heart So White is part of his family's history, though the rest is not, or not factually). There were no self-inflating pretensions of "it's so reductive to read this as autobiography!" It was merely, "well, yes, I use things from my life, but I trust my readers to know where one ends and another begins." (These aren't direct quotes or even paraphrases, but rather impressions—I had a shortage of paper and didn't feel like transcribing anyway.)

And Marías was more eloquent in extemporaneously articulating his philosophy of the novel and his own perceptions of his writing than many writers are with a prepared speech. In regards to the autobiographical origin of A Heart So White, he told us that he wrote the novel essentially to find out why the girl, the young wife, who killed herself did so, and he expounded on the common origins of the words "to invent" and "to find out"—both can be translations of the Latin verb invenire. He wrote the novel to push those two actions together, to invent a context for that action which would be satisfactory (if that is the right word) to him.

He spoke a bit about the nature of time, and I wish I had been taking better notes, but one thing that I remember that he said guided his work was the idea that the present is a future past—not terribly original, perhaps, but an idea which has a grammatical cast to it that I like (if one substitutes "future perfect" for "future past," which may have been what he actually meant). He also spoke of the novel as a "way to recognition," as opposed to a "way to knowledge." I wish I could reproduce what he said, but that basic dichotomy is quite obviously a fertile one.

Finally, he offered an interesting account of how he writes. After a page is finished—I don't believe he said "perfected," but he could have, not because he was less than humble, but because that would be an appropriate verb for his writing—he will not add new material or subtract anything from it to restructure the shape of the narrative. He says he will make continuity corrections (switching a Thursday to a Tuesday), but he doesn't change what he has written if doing so might make things more convenient for the novel at a later stage; if Marías didn't think of it the first time, he has to write his way around it at the point in the narrative when it becomes necessary to do so. If it might help, for instance, that a character knew something 20 pages earlier than when Marías thought about it, all the worse for the character—and for Marías—he described this method as "suicidal!" He sticks to this principle, he says, because he wants to parallel the conditions of knowledge in real life. Not knowing something when you're twenty has actual consequences, no matter how much you might wish you had known that thing now that you're thirty.

***

I have other things I should have been doing, but I did start reading A Heart So White the afternoon before the talk in order to get a feel for his prose, or for his prose in translation (btw, he expressed great admiration for his frequent translator, Margaret Jull Costa). It is an incredible book, and I'm a little sorry I started it as I can't really return to finish it until I get at least one or two papers done. I feel, as the pages turn, as if I'm plunging deeper into the story—or as if I'm in a dimly lit room and slowly taking note of individual items and curiosities as my eyes adjust. It's just wonderful.

***

I had already written the above when I ran across an excerpt from John Crowley's blog which also recounts the event and describes Mariás's writing regimen much better than my effort did. (h/t) I wish I had known what John Crowley looked like; I've been meaning to read something by him for some time, and it would have been nice to put a face to the (illustrious) name.

Later edit (12/7): I read Benjamin Kunkel's LRB review of the third volume of Your Face Tomorrow, which he finds to be a major disappointment relative to his earlier work, although I find his argument for this declension to be both confused and unconvincing. Basically, Kunkel comes off as objecting mainly to the genre elements of Your Face Tomorrow, pining for the older, purer works. Kunkel does do a marvelous job praising and describing those older works, though—just stop reading when he switches to talking about YFT.

Comments

What's more, the B-movie trope is a staple of ALL Marias' books... I don't see how a reviewer could talk about his work without addressing that theme.

I highly recommend the trilogy, but caution that it is probably a month-long job.

He does talk somewhat about the B-movie-ness of his earlier books, but it seemed to me that he excused it for Heart So White and Tomorrow in the Battle, viewing it as a less important or less dominant aspect, that other things outweighed and redeemed it.

I am hoping to read some more Marías soon--but I think I might start on some of the other novels first, and wait for the summer to tackle YFT when I can devote more time to it.

IMO, a good one to start with would be "When I Was a Mortal," which is presented as a short story collection but feels like something more.